Path of Light and Shadow Review

False Dichotomy – A Path of Light and Shadow Review

“You see, in this world there’s two kinds of people, my friend: Those with loaded guns and those who dig. You dig.” – Clint Eastwood, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

The logical fallacy known as the False Dichotomy regularly shows up in political rhetoric and in entertainment venues. There are plenty of good essays out there discussing the dangers of thinking in black and white extremes, but I’ve always found the most enjoyable examination of these ideas to be found in cinematic anti-heroes. I dig the man with no name. I’m sure that somebody smarter than I, could write a clever essay on Path about how the cruelty and mercy dichotomy is a false choice, but for me, I’d be happy with a solid game play experience, even if I don’t get to play the anti-hero.

Like many games before it, Path of Light and Shadow (Path) tries its best to bury the lead. You have the interesting design pedigree paired with the vibrant art of Beth Sobel. You’ve got these nifty little modular plastic tower pieces that function to track the defenses of a territory. You have a narrative that draws inspiration from A Song of Ice and Fire. But the big ticket item that Path hangs its hat on is the idea of its morality track. Much like the morality track players have seen in games like Fallout, Knights of the Old Republic, and Mass Effect, Path tracks player choices in the form of a Cruelty or Mercy “morality” track. Embracing either alignment fully can grant a player significant benefits and challenges. While the Cruelty/Mercy morality track is interesting and something that hasn’t been used in a deck building game before, it isn’t what makes Path shine. The real beauty of Path is that it is the first real time a deck building game has integrated TWO unique technology trees into a deck building game. Both Dominion and Thunderstone have flirted with the use of tech trees mixed with deck building, but Path absolutely embraces these ideas and turns them into something that feels quite compelling.

That doesn’t sound very sexy, but once you sit down with Path, the tech trees quickly emerge as a breath of fresh air in this design. Path’s first tech tree is the kind you would come to expect in most empire building games. You have 5 categories of technology (called buildings). Unlocking the first level of a tree gives you a cool special power and allows you the choice of unlocking a second level power too, and so on. You develope your tech tree by playing cards out of your deck much like you would expect to do in any normal deck building game. While that doesn’t sound revolutionary, I’m not aware of ANY deck building games that do that. This normal tech tree is quite robust and offers significant decision points to players to explore strategies over multiple plays.

That doesn’t sound very sexy, but once you sit down with Path, the tech trees quickly emerge as a breath of fresh air in this design. Path’s first tech tree is the kind you would come to expect in most empire building games. You have 5 categories of technology (called buildings). Unlocking the first level of a tree gives you a cool special power and allows you the choice of unlocking a second level power too, and so on. You develope your tech tree by playing cards out of your deck much like you would expect to do in any normal deck building game. While that doesn’t sound revolutionary, I’m not aware of ANY deck building games that do that. This normal tech tree is quite robust and offers significant decision points to players to explore strategies over multiple plays.

The second tech tree is your deck itself. Every card in your deck is a person. Each person in your deck can be “leveled up” by swapping it with a powered up version until you reach the end of that character’s development with a single super powered card. Effectively, your deck is simply a chaotic tech tree you will customize over the course of the game.

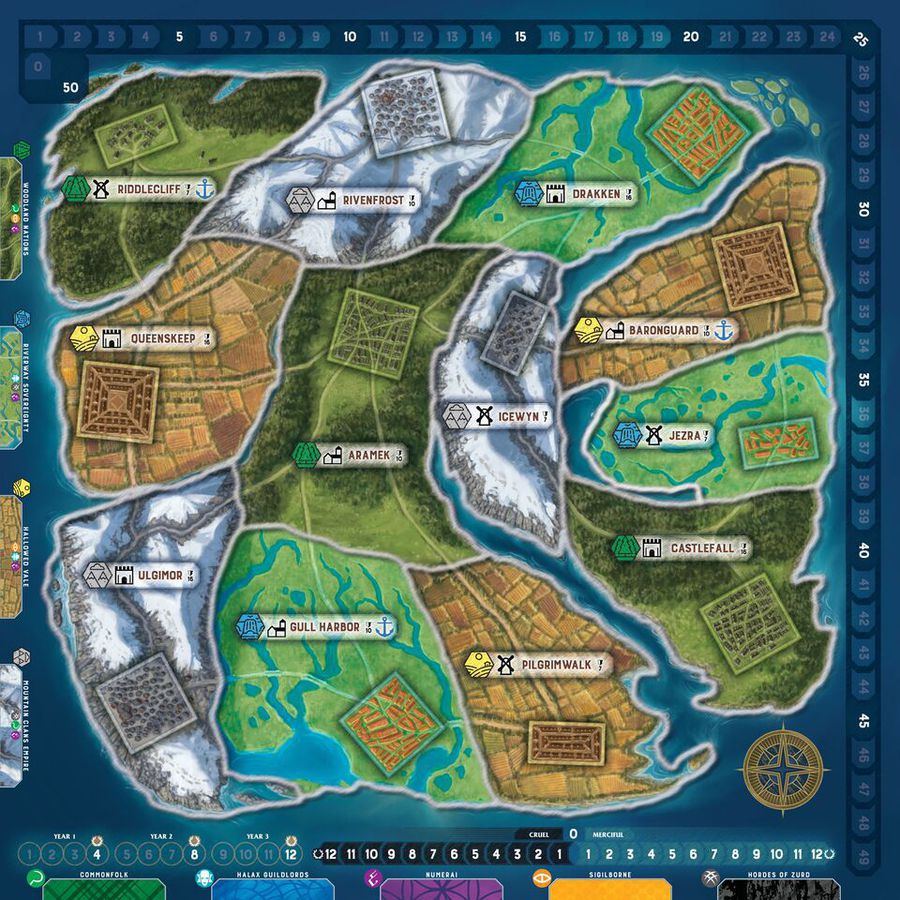

If you’ve played enough deck building games over the years, you’ll recognize that most deck builders use one of two types of markets: The Dominion fixed market or The Ascension rolling market. In Dominion your choices of cards to buy are fixed throughout the game. In Ascension, the cards you can buy are ever changing. Occasionally, you’ll see a game that tries to do something completely different (like Princes of the Dragon Throne, or Magnum Opus) but as a general rule the most successful deck building games follow those two types. Path’s tech tree style deck building offers a completely new way of constructing your deck. The easiest way to add cards to your deck is to gather random characters. This is done through conquering territories on the map or by ending your turn in certain areas on the board. The type of territory you conquer or recruit from determines which randomized deck you are pulling cards from, each of which is seeded with different factions of character cards. While this sounds pretty random, in practice, there is a definite strategy in positioning your army in specific territories as a way of controlling your deck’s evolution, which is something I’ve never seen done in a game before and is quite interesting.

The more rewarding way to build your deck involves improving the cards in your deck by promoting them to “leveled up” versions of themselves (as described above). The acts of gathering cards and improving them is wholly unique to Path and one that I hope to see copied by other games in the future. This balancing act is a unique and very satisfying puzzle to unwind over the course of your game.

By almost completely removing player choice over the low level cards added to their deck, Path is trying something radically different from most all of its predecessors. Traditionally in a deck building game, cards are added to a player’s deck through choice (players draft or purchase a specific card) or as a punishment (think curse cards in Dominion or wounds in Legendary). Path forces players to take randomized low level cards, but then gives players choices of how to deal with these random cards. In practice, it works brilliantly. Every card in your deck has some value and how you choose to leverage that value is where the game shines. Each five card hand you draw is filled with choices and opportunities you can take advantage of. Do I level up my tech tree? Do I level up my weaker cards? Do I cull my weaker cards? Do I take over this abandoned fortress? Do I fight my opponent with the intent to win battles or am I simply culling my deck and hoping to wear down her defenses? There is a very impressive strategic depth in the variety of options available to players. The biggest advantage Path has over Tyrants of the Underdark is the raw diversity of choices that open up for players.

While this abundance of strategic choice is great for replay, it also happens to be one of Path’s greatest weaknesses. Path can have an overwhelming learning curve and may cause significant AP for players through the first half or so of their first game. Path isn’t a hard game to grok, but the volume of choices that are immediately available from turn one can be quite overwhelming for players trying to learn the game. Once everyone is on board with the game, my experience has been that you can easily get through a game in 60 to 90 minutes. That is an impressively swift time for a game with this much under the hood. I will gladly take this learning curve if it means that I’m going to have added replayability without the game going stale. So far, Path really has held up nicely to repeated play. Ideally, I think it might be nice to add another line of cards to each of the 4 main factions along with more advisers, allies, and Numerai, but an expansion is not necessary for this game to feel whole and complete.

“If you’re not with me… then you’re my enemy!” – Anakin Skywalker, Revenge of the Sith

I would be remiss if I didn’t at least briefly mention the combat mechanism built into Path. I am EXTREMELY satisfied with Path’s combat engine. Without going into extreme detail, combat balances a satisfying bit of predetermined stats and dice chucking. It is very easy to understand once its been explained to a  player, and is sufficiently complex without taking too much time away from the normal flow of the game. Combat allows for just enough player choice and interaction without ever feeling frustrating or mean spirited. Path’s combat ranks up there for me as one of the best combat designs in recent memory, and again, I hope other game designs borrow from it.

player, and is sufficiently complex without taking too much time away from the normal flow of the game. Combat allows for just enough player choice and interaction without ever feeling frustrating or mean spirited. Path’s combat ranks up there for me as one of the best combat designs in recent memory, and again, I hope other game designs borrow from it.

I try to avoid talking about components unless there is something remarkably good or bad about them. Unfortunately, there are some very annoying component issues worth noting. The fortress pieces are perhaps a bit too abstracted for my tastes. I would have MUCH rather that the game used cool castle or fortress minis with dial bases to track defense/damage al a Mage Knight. The pieces that come in the game are functional and can give you good information at a quick glance, but they detract from the aesthetic of the board a bit too much for my taste. It doesn’t help that the fortress blocks are often slightly warped and can be difficult to snap together or don’t sit flush with the game board. The most egregious component issue though are the fragile standard peices that players use to mark provinces they control. If you try to fit it into the top of one of the fortress blocks too hard, you are likely to break the standard at its base. The standards are a VERY important component and unfortunately they are very easy to break. A different plastic should have been used to make these bits.

My last component gripe is something MANY games do wrong and that is the layout design of the card backs. The card backs use a cropped version of the box cover art. I always hate to see box cover art on my card backs (it feels trashy) but the publisher somehow figured out the worst way to crop the box art and the image is horribly framed on the back of the card. Its awful, and if I were Beth Sobel I would be angry at how my art were being misused. Somebody needs to go speak with Stephen Gibson over at Green Brier Games about how to correctly design a card back.

It is with a very heavy heart that I have come to the conclusion that the Mercy and Cruelty track is probably one of the weakest design elements buried in Path. The morality track is a definite improvement on the morality track found in Near & Far or Above & Below because playing the villain is absolutely a valid strategy. Red Raven Games takes a definite stand against what it deems to be the wrong decisions. Mechanically, though, the cruelty/mercy track is a false dichotomy. Your choice feels like it has little meaning so long as you commit to your given philosophy. Choice in Path is far more abstracted (than Red Raven Games titles) as the things that effect your morality are hidden a bit behind game mechanisms with very little flavor text to explain that culling cards equates to killing people. The real problem with Path’s spin on the morality track is that a neutral morality just isn’t a viable player choice. Fully committing to one world view or the other is not only easy, but it should be generating a player victory points by the handful as early as a third of the way through the game. A player who chooses to remain neutral lacks the pure VP generating potential and deck efficiency of their opponents who commit to one side or the other. This disappointment doesn’t diminish the things Path excels at, but it is something I find puzzling given how prominent the morality track is advertised in the game’s promotional material. It would be interesting to see the designers explore this in future expansions.

“Good, bad, … I’m the guy with the gun.” – Bruce Campbell, Army of Darkness

Path is a fun game because it allows players great strategic choices through the development of its tech trees, and the evolution of the player’s deck. It offers solid positive feedback loops where the player is constantly rewarded for their efforts and the game can generate a very real sense of empowerment and progression over the course of the game. If you enjoy deck building and area control games then Path is a solid choice for you and worthy of a place in your collection. Path is a solid game design that feels well tested and polished. It is a compelling area control experience that is filled with new and interesting ideas, but manages to keep the play time at a lean 60 to 90 minutes.

Fans of area control and meaty deck building games can buy with confidence. BGG Rating 9.0

Scott Sexton

Scott Sexton is an avid boardgame enthusiast who regularly posts reviews on BoardGameGeek - You can subscribe to his Review Geeklist here and check out his contributions to Brawling Brothers here.